As a multimedia artist with multiple interests, Sel Kofiga draws inspiration from how our environment, spaces, bodies and objects are all interconnected and questions the world. It was the vibrant energy of the markets he grew up around that led him to his work highlighting the realities of the people who worked there.

The Accra-based artist started the Slum Studio from the kayayei experiences – Ghanaian term for a female porter or bearer – as a way to retell the stories of secondhand clothing redistribution in his country, Ghana. His photos and upcycled designs – made of second-hand clothing waste found in the markets – show his perspective of a business that sees 15 millions used items every week in Ghana. The OR Foundation – a US-based non profit exploring the second-hand clothing trade in the context of Accra, Ghana through their research project “Dead White Man’s Clothes” – estimated that only 40% of this volume is sold to wholesalers while the rest will be sent to landfills or burnt due to their very poor quality.

In this conversation, Sel Kofiga tells us how he uses his platform to raise awareness on this environmental issue and challenge the status quo.

You are a multidisciplinary artist working with photography, performance and even video installation. How did you get into fashion? What motivated you to create Slum Studio?

I’m a self-taught artist with a background in sociology and I’m very inspired by spaces. One of the most important places I grew up exploring was the market space. It was always bursting with energy, and diversity. So many people coming from different parts of the country ended up there. I loved being around that energy! As an artist, I naturally came to explore this specific space in my work.

That’s how the Slum Studio started in 2017. I was interested in people we call the kayayei. They are young women and men, but predominantly women, who are getting paid for travelling from different parts of the country – especially from the northern region to the southern region – carrying goods on their heads.

I had been familiar with their work since my childhood. But as I became an artist, I wanted to explore it with more depth. When I was doing this photo series of their activity from 2017 to 2019, I quickly realised that one part of their work was very connected with fashion. And by fashion here, I mean second-hand clothing. They would carry bales from different warehouses to different parts of the market.

I focused on this aspect of their work, documenting their everyday life. I would go to their houses to ask them about this business and how it affected their lives. This intimate exploration made me realise how key their role was in the secondhand clothing redistribution in our country.

Awareness and education prevails in your work. What message do you want to convey with Slum Studio?

The Slum Studio is a multifaceted brand addressing the politics of clothing where I explore second-hand clothing purchase and redistribution in my country, Ghana, through visual art and storytelling.

I’m interested in talking about people more than anything else with this project. I try as much as possible to tell the stories of what goes on in the market. I want to highlight this specific space, showing who are the people involved, what roles they are playing and how this business is affecting our environment.

From thrifters to merchants, the story always starts from the people in the market who are in the business of second-hand clothing.

I create images of the market where I show how they use their creativity and imagination to sell these pieces to provide for themselves. I try to talk about the local economy and how it is actually being boosted by these products that have been used by other people in the world.

Like the merchants in the market, you also create fashion pieces yourself to tell these stories. Can you tell us more about it?

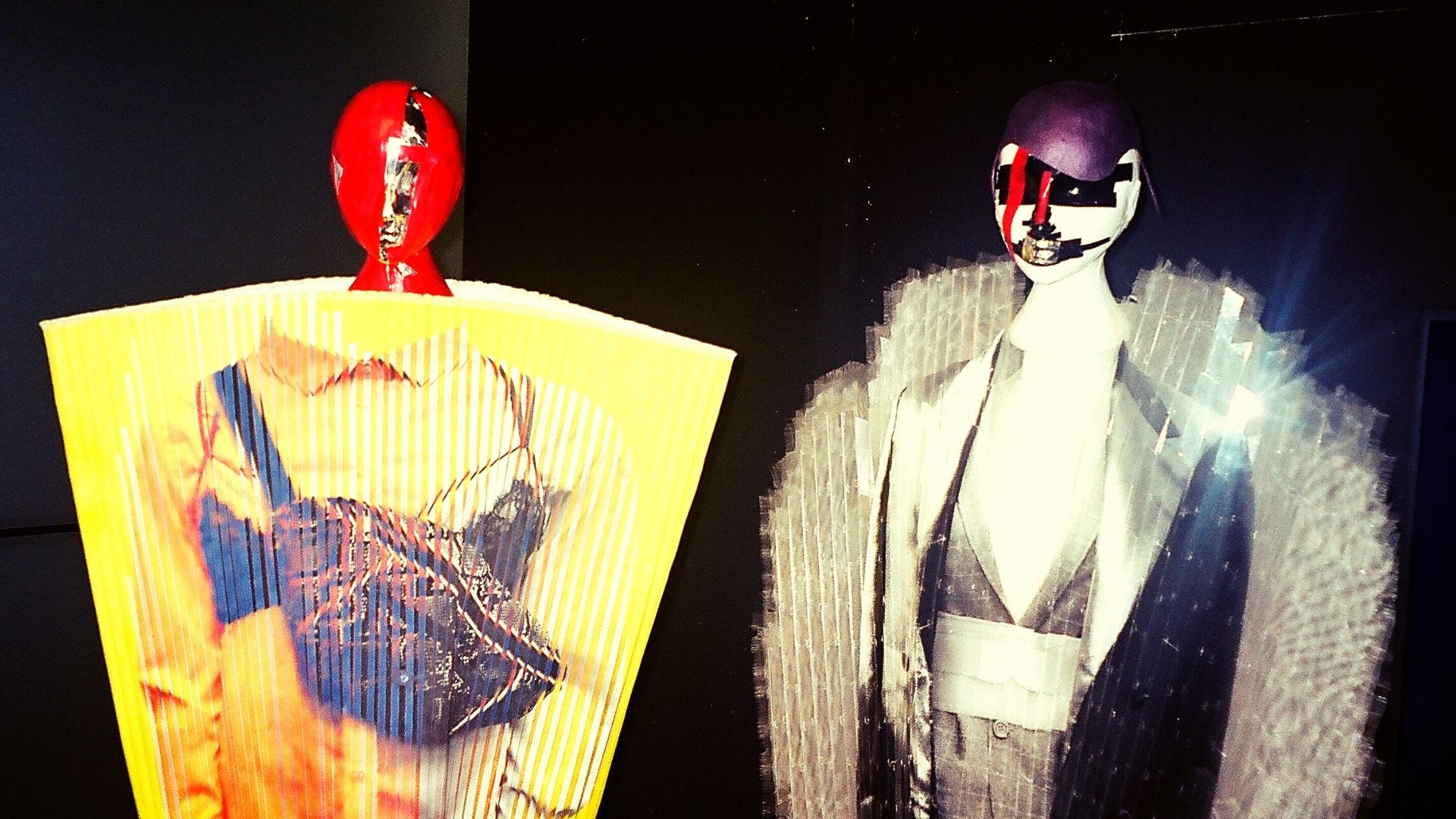

I’m a painter of abstract expressionism. Alongside image making, I also collect offcut fabrics from the second-hand clothing market that I rework in my studio by hand-painting them. Hand-printing stories on fabrics is something I grew up seeing in our traditions. I try to bring that back into my practice by translating the stories I capture into abstract imagery.

Throughout my documentation, I also try to incorporate the different subjects I want to touch on through my artwork as an artist. The question of gender is one of them for instance. I want to convey the idea that everybody should be received and respected. Child labor and unemployment are also topics I really want to talk about because of the kayayei’s living conditions. They often start this work from a very young age, as young as 8 to 16 or 17 for the oldest.

How has this project been received locally?

The response has been brilliant so far even though there is always room for improvement. The words “sustainability”, “upcycling”, “recycling” are not new at all to people here actually. Making something out of waste has been our lifestyle for a long time.

That’s why I keep saying I’m not the first person doing this and I’m not going to be the last one. People have been beautifully doing it for ages! People would buy cheap denim jeans and paint them to sell them at a better price for instance. This is basically what the Slum Studio is also doing. For me, it’s just another way of contributing to a system that people are already well aware of. I’m just doing it my own way.

I’m glad that it is exposing a topic that people were not really interested in. I hope that in the future, people will pay more attention to it and become more conscious of how they use things. I also wish the government will step in at some point to put regulations in place to limit – not ban – how much second-hand clothing comes into the system.

You were saying that respecting clothes was already in the culture. Does your work around awareness and education speak more to the West? Where do you position yourself in this conversation?

I’m a global citizen. I could be doing this work everywhere in the world because second-hand clothing is everywhere. For me, all regions of the world are part of this. From Singapore to South Africa, we are all playing a role in this system, all of us are complacent.

The Slum Studio is a space where people can connect to how they consume and displace things. I’m speaking to a global audience, taking Ghana as a starting point. Beyond fashion, I want people to see how these goods wasted in the West are very much affecting us here in the South.

We talk a lot about the waste coming from the West. But we also need to be mindful about designers’ practices on the continent to avoid falling into the current situation that originates in the West. Are you also witnessing patterns of waste in garments production processes on the continent?

Of course! There is a lot! That’s a topic I will be working on in my next project. I’ll try to understand how much waste is produced here from the fabrics used by our designers, tailors and even our thrifters. And this waste is not only reduced to textiles. When you think of batik and tie & dye for instance, people often use chemicals that end in our water and ultimately pollute the land.

If I take the Slum Studio for example, I usually create new pieces from the offcuts I produce. Obviously, I’m not perfect at it but I try my best to make sure that at least 60 to 80% of the waste I produce can be used for something else.

It’s always a work in progress.

Indeed. That’s one of the reasons why I don’t like saying I’m a fashion designer, not in a bad way. But I feel like most fashion designers have a very limited take on what they produce. I feel like their main focus is limited to the design. Sometimes, they will do whatever is needed to get that one piece done in that one specific fabric without taking care of the environmental impact of that fabric.

Are there other independent initiatives like yours raising awareness around second-hand clothing?

The first people I would probably mention are the people in the market. Most of us get our inspiration from their beautiful creative energy they use to create something out of the waste presented to them.

From the little time I have been into this, there are two people whose work I know. The first one is AfroDistrict which is also a brand. They also try to talk about secondhand clothing in many different ways. The second one is Get up Stand Out who is a stylist. He has always been interested in the ideas of reusing, reducing and restyling with secondhand clothing. He has always been into thrifting and styling people with clothes from Katamanto market – the premier destination for second-hand clothing in Accra and all Ghana. And of course there is the OR Foundation which has been doing amazing work for some time now.

How should we expect to see the Slum Studio evolving?

I would say that I don’t want the Slum Studio to be known just as a fashion brand. In the future I’ll keep on documenting the second-hand clothing business but I’ll probably stop making these beautiful pieces that people fall in love with. As mentioned before, I’m going to start researching and documenting the waste we produce locally when it comes to fashion. I want to make more sculptural pieces out of that waste.

Ultimately, I want people to understand that the Slum Studio is there to create awareness about waste and incite people to practically do something about it. Together we can all solve what is going on. I want to work with more people, I want to create workshops where people can also engage with my work and engage with what goes on.

Then one of the things I really aspire to do is making sure that as many kayayei are taken out of their business and taken into vocational training where they’ll be training for themselves. It’s not easy at all but I really want to contribute to that too.

About Stéphanie Chendjou

Stéphanie Chendjou is a fashion writer with a strong passion for African markets. She enjoys sharing creatives’ stories and insights of these diverse markets at ndaane.com. On top of her writings, she’s experienced in project & operations management in fashion & luxury. She’s currently based between London and Paris.