So far 2020 has been very challenging as much on a social scale as on a political scale. Hence, it is an opportunity to question all our models and re-adapt the rules so it can be relevant in the upcoming years. The fashion industry needs a huge reformation, no surprise on that. A lot of aspects need to be rethought, but today I’ll focus on an issue that is crucial for me: the cultural appropriation occurring in the fashion industry. This subject has been mentioned for quite a while now, but nothing has really changed. Similarly to the deforestation, it is the kind of problem that is pointed but not solved. What is very annoying in our times, is the fact that a lot of issues are underlined, but it is a real challenge to find concrete actions to suppress them. When it comes to the African culture, the misinformation is truly real. This lack of reliable and concrete knowledge is the reason this appropriation is still possible today. As the goal of this article is not to mention problems without proposing solutions, I will also explore the possibilities we can consider in order to avoid cultural appropriation. But first of all, a definition of this concept seems necessary.

Cultural appropriation refers to the ‘the unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, etc. of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society.‘ This concept implies the use of cultural codes of social minorities by a dominant group. The main issue with such practice is the fact that the elements used are often – in fact always – put out of their social context. Most of the time, cultural appropriation is about taking a piece of one culture without caring about the history and insights behind it. In an essay named ‘Les masques noirs des pop stars blanches: Miley Cyrus et les politiques de l’appropriation culturelle‘, Keivan Djavadzadeh underlines the fact that the notion of cultural appropriation goes hands in hands with the term color-blindness. For him, the two concepts are depending on each other. The general psyche promotes the idea that we live in a time where the color or the origins are not important and don’t have an impact on individual’s social paths. However, this assumption is easy to deconstruct. We just need to look at the western society functioning to highlight rooted discrimination and racism mechanisms. Believing our current society is above cultural appropriation and that it is submitted to the color-blindness logic is very naive. Every aspect of our social life is influenced by our heritage and appearance. Blackness is widely used in the mainstream medias and individuals are often excluding all the difficulties and struggles that come with being part of this community. Along with the microaggressions experienced on a daily basis by black people in the western world, our evolution in the social life is deeply influenced by the perception of our culture. The prejudices passed from a generation to another are still alive.

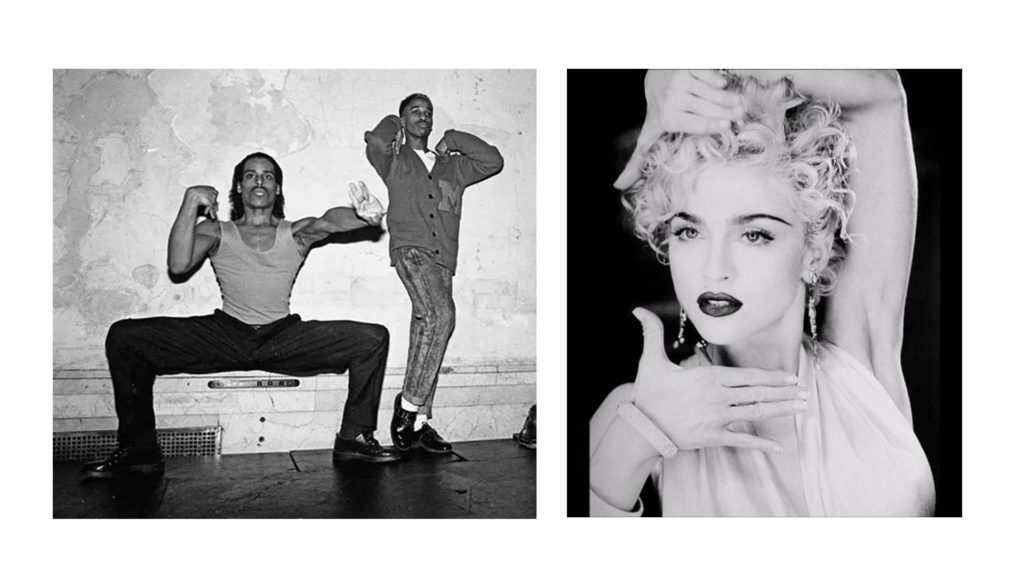

In this essay, we are going to focus our analysis on the cultural appropriation of blackness and African culture occurring in the fashion industry. What is essential to remember and to understand while reading this piece is that the point is not to place one culture as better than the other. Indeed, the goal is mainly to show why this practice in the field is problematic and to eventually bring solutions to tackle this issue. The cultural appropriation towards black culture is not new for sure. We could quote a lot of examples of this phenomenon happening in the music industry for instance. During the 1950’s – 1970’s, Elvis Presley used the codes of black rock culture to shape his own image. He even admitted that colored people were dancing and playing rock’n’roll way before he started doing music. The only difference is that people began to care when Elvis popularised it. In the same line, during the 1980’s, Madonna used voguing which was initially a dance that appeared in black queer clubs in Harlem. While we could think this is simply the process of sharing cultural proprieties – in ideal, one culture influenced by the other in a well balanced context – this mechanism caused deep and rooted issues. Indeed, while referring to the history of Rock or Voguing, the popular psyche will first mention either Elvis, either Madonna. The damages made on the history of those cultural products are tangible. Rare are the people that will quote Chuck Berry as the King of Rock for instance. Building a history by suppressing the contribution of minorities is a usual approach used in the western world. They shape a history which ends up so well implanted that lies are buried away for centuries and consequently for generations… Until we decide to go on a hunt to find and build academical resources.

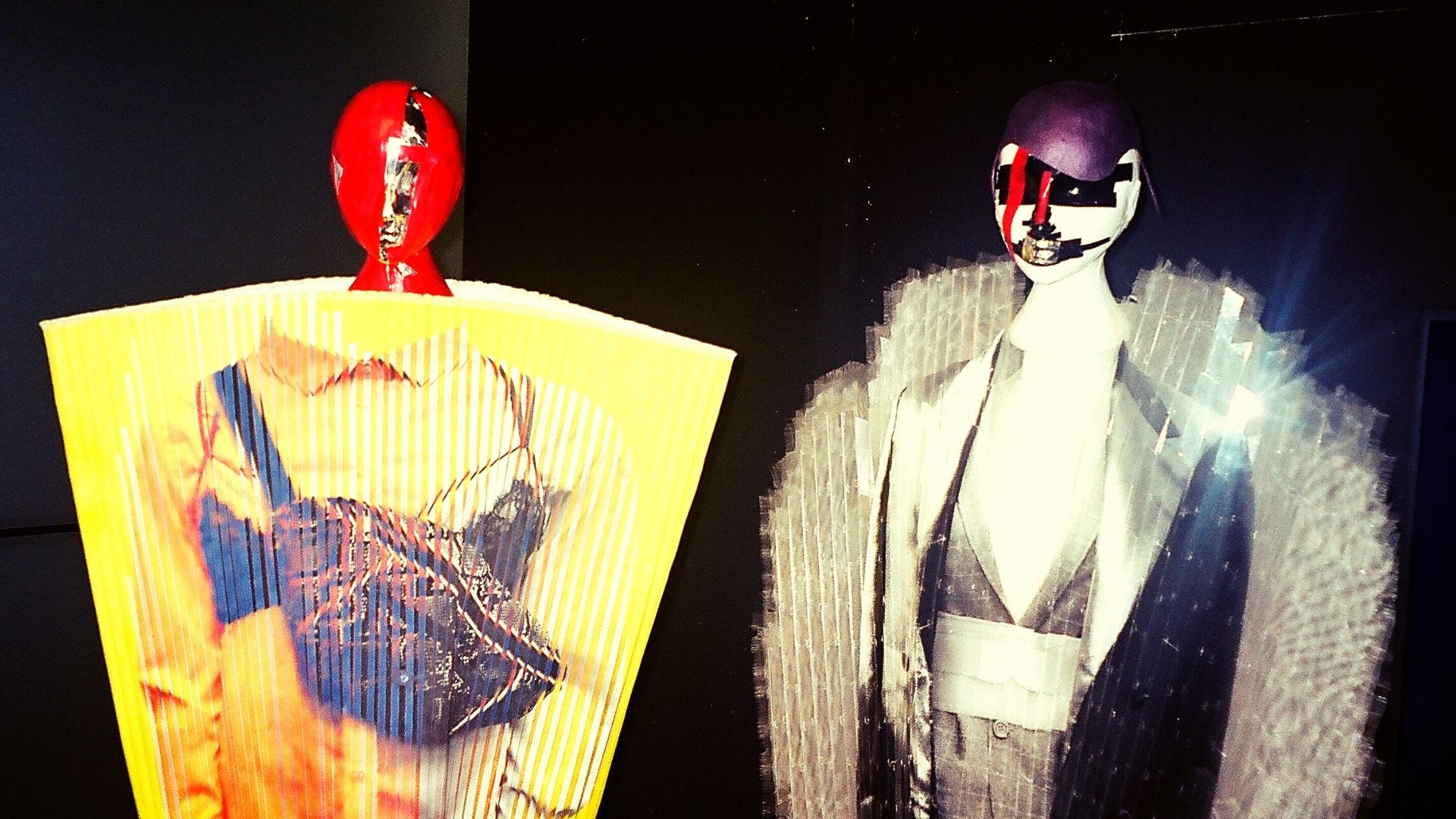

Although cultural appropriation has been largely exploited in the fashion industry in the past – by Gucci, Marc Jacobs, Chanel, Givenchy, Balmain and so on… – throughout the last few years, the term has been deeply discussed in the public sphere. Before a certain time, it wasn’t really a moral issue for brands. Indeed, this phenomenon was undertaken by a lot of labels and the audience wasn’t shocked about it. As I mentioned before, many cultures which are contrasting to the western ones are concerned by the cultural appropriation. For example, Romanian traditional patterns were copied by Dior in 2017 (Pre-Fall collection). However, I chose to focus on the African aspect of cultural appropriation in the fashion industry because I am directly concerned by it, thus this is what I know the best. Each season we can see this problem coming back with less and less consideration from the designers at the origin of such rudeness – recently it was Comme des Garçons’ turn with these offensive and controversial wigs. Although it is easy to be pessimist when it comes to cultural appropriation, we have to admit that recently, more and more people seem to be aware of this issue, but only a few real actions are taken. Perhaps the solution would be to create organisations able to judge the level of fairness by studying concrete data along with specific criteria that are able to evaluate the degree of equity in the exchange.

While there is a lot of cases we could study to underline the lack of proper actions to avoid cultural appropriation, I think the Dior Cruise 2020 collection is a relevant example since they managed to get away with their responsibility towards the African communities by publishing an empty and meaningless video showing the designer Maria Grazia Chiuri ‘interviewed‘ by the model Adesuwa Aighewi. This event illustrates the perfect mechanism used by brands such as Dior to justify their flaws and incapacity to provide concrete information when it comes to the use of others’ cultural symbols. This case is at the same time delicate and tricky to tackle – as it bases its complexity on various insights that can highlight the lack of clear and concrete actions. First of all, to evaluate the reliability of this interview, it is crucial to understand where the intention comes from. The well-known model and auto-claimed activist, Adesuwa Aighewi was part of this show, so she logically has seen the collection before the official event during the fitting session. At no moment, before or during the show, she found useful to make a statement about the controversial aspect of this collection. It is after seeing the public reaction, Maria or/and her decided to make this short video trying to explain the concept behind the collection.

According to Dior’s creative director, this collection is a way to promote African craftsmanship and to underline the various ‘techniques‘ around the world. ‘I like the idea of objects and techniques traveling’ (…) That is what I really like, it’s what we have in common ground with other cultures” Maria explained. But when you look closer at the collaborations they made, one of the main expert specialised in African prints is not even someone that comes from the continent itself. How are you supposed to educate yourself by asking to the wrong person? How can you engage a fair-trade relationship in Africa, when the contact you have with the continent is through westerners? Even when explaining the concept behind Dior’s collection, the print expert makes a lot of faux-pas in my opinion. ‘she (Maria) wanted to really show the quality and the talent of the African Industries and to show that there are people who have skills, who can do luxury, valuable, quality products’, justifies her collaborator. This type of argument is not suggesting any concrete actions that can unravel the cultural appropriation accusations. Nevertheless, it underlines a cliché very present in the western world: ‘Africa doesn’t have any knowledge about crafts, luxury or the art of clothing‘ This idea simply suggests that this land is savage and that knowledge or savoir-faire cannot come from it. An expert that is from the continent in question will probably quote reliable resources to underline the history of those practices within the various countries. However, in that case, it is as if they are saying ‘Africa has ALSO talented people‘. The right approach would have been to show the history of art and crafts in the continent. A simple example would have been to quote the beautiful biography of Amadou Hampâté Bâ ‘Amkoullel, l’enfant Peul’. The writer tells us everything about the relationship with crafts in the upper classes of African empires. His own old brother used to learn how to decorate garment as a noble practice. Without hiring the right person – that has the proper knowledge – you cannot have the correct information to build reliable and interesting products. But besides this negligence, the financial contribution given to the community is still unknown.

Additionally to this pointless expertise, Maria was supported by the half Thai half Nigerian model, Adesuwa Aighewi. She proclaimed ‘I am African, I’m Nigerian I personally don’t think it’s cultural appropriation. I thought it was a very beautiful blend of the Western world and the Old World coming together to make something beautiful. To unite the bridge between you know, West and here (Africa) which is such an interesting conversation these days, where everyone is saying cultural appropriation this, cultural appropriation that. But I think that when you do things like this, you’re starting a conversation, you’re bridging the gap. Now Africa isn’t like the mystical place that no one knows about (…) Now with the exposure with Dior we can have a conversation‘. By suggesting that it was not about cultural appropriation, she placed herself as a lawful judge capable to make this vision general and unquestionable. As if her perception was not blurred or influenced by opportunism. Speaking of bridging the gaps between the culture seems so vague. One thing that is important to mention is the fact that she, at the same time, embraced the need to be validated and used by Dior in order to be seen. The validation of westerners is placed as a step to pass. As if they are gatekeepers to seduce in order to enter into the fashion world. African history needs to be validated by such structures to leave the state of ‘mystery‘. Unfortunately, even after this empty contribution, African culture and history is still a mystery to a large part of the western world since a few tangible evidence and research have been taught. Misconceptions about Africa remains. To avoid things to be unchanged you must deconstruct the total scale of beliefs by giving reliable facts.

You might think that she did her part and it is enough – since it comes from a genuine sentiment. However, a question remains? Why didn’t she act before and during the show? Why wait to see the public reaction before acting? Do I need to remind you of Ayesha Tan Jones‘ action and statement during Gucci SS20? She didn’t wait the end of the show to claim her opinion on the use of mental health as a trend. She did it on set, denouncing the brand live, proving that her commitment isn’t fake nor opportunist. It is always a matter of authenticity isn’t it? So easy to fake and so hard to evaluate…

While this interview finished on a vague questioning on feminism, it let’s us without any real data on the contribution and credit given to communities she took inspiration from. After all the question of who gets the profit is the most important. How much the community in question perceived on the profit generated from the collection? In fact, juxtaposed to the Cultural Appropriation, Dior is also responsible for Cultural Exploitation. According to Richard A. Rogers, this notion is referring to ‘the appropriation of elements of a subordinated culture by a dominant culture without substantive reciprocity, permission, and/or compensation.‘ The terms of ‘reciprocity, permission, and/or compensation.’ are very crucial in this definition as they underline the necessity to be validated by the community concerned. This idea going against Adesuwa’s statement about Dior bringing the spotlight on these technics. The latter are owned by specific ethnic/social groups that don’t need to increase their visibility among westerners but tangible and concrete financial actions.

Making African culture so easily appropriable to galvanise and bring exoticism to your brand is a true lack of respect. It makes the structure so disposable that it weakens the culture itself. Treating cultural objects in such an insignificant way – by excluding all the social implications this approach involves – is a sign of deep lack of consideration made by the West towards the African cultures. While this could be just a vague concept or an assumption, social studies underline the fact that this disposable aspect – that lead to the cultural exploitation – can be explained by historical facts. Among those academic resources, Buescher & Ono explored the concept through a colonised layer: ‘Cultural exploitation includes appropriative acts that appear to indicate acceptance or positive evaluation of a colonized culture by a colonizing culture but which nevertheless function to establish and reinforce the dominance of the colonizing culture, especially in the context of neocolonialism‘. The important part of this definition is the ‘context of neocolonialism.’ We are all aware – I hope – of the fact that colonisation was not only about taking possession of your bodies but also your souls, traditions, belief, values and so on… This approach was embracing the totalitarian logic. In this same logic, practices, technic, cultural objects from the colonised communities was made disposable for the colonising culture. This approach remains the same today where neocolonialism is feed by western capitalism. This explains the deep lack of consideration towards those cultures and also the disposable aspect they reflect.

For now, until we are not able to deal with those traumas and issues, we cannot use the African culture so easily, since it is now a political commitment. We cannot shy away and deny the social aspects of being African or black in the western world. Neglecting those experiences is a very dangerous practice that give permission to the audience – in the case of a brand – to exploit the cultural symbols of other communities without considering them in the entire process. As I mentioned before, the first thing a fashion label should do when they want to use foreign patterns is to give tangible proofs of financial compensation and consent from the community. Without those concrete actions, I cannot see a possibility for cultural appreciation to be a concept itself. In an I-D video, a group of London-based creatives are trying to give a definition of cultural appreciation by comparing it with appropriation. While their propositions goes in line with what is exposed above – give credit to the people of the culture, consult people from the culture, work with the people of the culture – one creative underlines the fact that ‘ I don’t feel there is actually a need for another person that isn’t part of my culture to now go and represent it. Just let the people that actually of the culture talk‘. I really think this statement sum up the all situation. For now, the perception and the representation of African culture are not accurate, especially in the western world. Thus using its symbols, textile and technics seem inappropriate when you’re an external actor. A culture is defines by its people, therefore, they are the lawful storytellers, able to pass and share the narrative around their history and culture. As long as we are not listening to the people concerned, I cannot see a future for cultural appreciation in the fashion industry. Currently, this field is truly unfairly balanced and it doesn’t allow such concept to blossom. This opinion might appear as radical, however, after experiencing personally the problem – there are no systemic changes without deep restructuring.